Environment

Why mountains matter in Canada

They sustain us, enrich our lives and inspire us

- 1287 words

- 6 minutes

This article is over 5 years old and may contain outdated information.

People & Culture

Four expeditions, funded by The Royal Canadian Geographical Society, went to physical extremes this year to further our understanding of Canadian geography. And while three of those journeys have finished, the fourth will continue this October, when a team of nine adventurers is set to return to the Mount Tupper cave system. To date the cavers have mapped 2.3 kilometres, climbed more than 190 metres and dived through three sumps (water-filled passages connecting cave chambers). Canadian Geographic caught up with expedition leader Nicholaus Vieira.

Can Geo: What obstacles have you encountered in the cave?

Nicholaus Vieira: The sumps are definitely throwing a huge challenge into the expedition because they affect how many team members can go further into the cave. After the first sump, we were expecting to keep climbing up through waterfalls, but instead we had to swim through two more passages. The next obstacle is the fourth sump. And we have not found the end of them. Sump four is the longest sump hands down in the cave system so far, so passing it will require a different style of diving than the others. We don’t know how big it is. The first three sumps have been relatively short — 20 metres — and we can get through them with one scuba cylinder. With this fourth sump, we’ll need two cylinders for every diver.

When we surface on the other side, we’ll have to start climbing. I’ve been talking to Parks Canada about permission to camp underground beyond the fourth sump. That way, we could stay there for two or thee days, be more productive and not be completely knackered.

Can Geo: The expedition has been collecting microbial samples from the cave. What have you learned?

NV: We are working with Naowarat Cheeptham, an associate professor of microbiology at Thompson Rivers University in Kamloops. Her team has been able to isolate 266 bacteria from the samples. They’ve tested 80 of them so far to see how they react to bad bacteria and eight of the 80 tested samples have shown resistance to staph infection. These microbes could potentially be used to create antibiotics against the infection.

Can Geo: What is the goal of the next stage of the caves?

NV: We’re going to try to go as far as we can: ideally to Tupper sink. If we could do that, everybody would be thrilled. We’d also like to get a better understanding of the geology of the cave. We’re talking about dating the cave formations, the stalactites and stalagmites.

We’ve only set up Petri dish samples in the front part of the cave. We’d have to set up more samples further in.

Can Geo: What will be the greatest challenge when you re-enter the cave?

NV: Sometime in November, Parks Canada’s avalanche control will move in on the mountain. When that happens, we won’t be able to camp, and all trips will become day trips. That means we’ll have to move very fast through the cave to get as far in as possible and all the way back out to your vehicle by midnight.

Another hurdle would be if sump four turns out to be really long or ends up in a boulder choke where we can’t squeeze through to the surface. If that were to happen, we’d have to decide: do we start digging under water? Or do we start working on some higher fossil bypass? After the fourth sump, we’ll have to climb in an active waterfall, which can be challenging, especially when you’re in a mild state of hypothermia.

Can Geo: What would happen if something went wrong?

NV: If we had an immobilizing injury beyond the first sump, it would be a very, very challenging rescue, because we would have to take somebody through the underwater section in a stretcher. It can be done. What I’ve told the other members is that we’d drain that sump. We’d bring in a pump and we’d pull all of the water out.

If we’re further into the cave, it eliminates a lot of other people from being able to assist, because they wouldn’t be able to use their regular rescue techniques. The saving grace for us is that it’s a very large cave. We don’t deal with many squeezes or restrictions. Unfortunately, all of those are underwater.

A rescue can be done, but it would not be easy. Parks Canada makes you sign a waver saying we’re beyond all rescue capabilities.

Can Geo: It sounds dangerous. What motivates you to do this?

NV: My personal goal is to try to make caving mainstream and to educate people about these places. They’re not protected. Some very, very rare ones are, but nobody is aware of how important they are. Many people like to go into caves and have fun — that’s great — but be safe and understand what you need to do for conservation purposes.

My goal is to get more people to understand the archaeological and the hydrological importance of caves. Twenty-five per cent of the world gets their drinking water from these places. These are underground rivers; these are entire ecosystems. NASA’s interested in these places because of what we’re finding underground and training for the astronauts. They do studies on cavers to see how people react in a highly stressful environment separated from the surface and all that kind of stuff.

Read more about the Raspberry Rising expedition or learn about the Royal Canadian Geographical Society’s expeditions program.

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

Environment

They sustain us, enrich our lives and inspire us

Exploration

Caving: The ultimate underground sport

Exploration

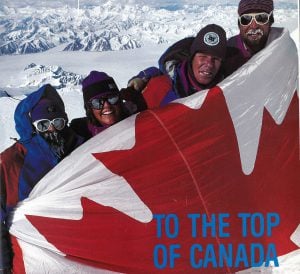

In 1992, a team backed by The Royal Canadian Geographical Society became the first to accurately measure the height of Mount Logan, Canada’s highest peak

Places

In Banff National Park, Alberta, as in protected areas across the country, managers find it difficult to balance the desire of people to experience wilderness with an imperative to conserve it